Architecture in Lockdown: Case study III – Breathing cities

Workshop A Green House at Boisbuchet led by French-French-Lebanese architect Lina Ghotmeh, 2017, © Mariana Lopes

Taking a side-step from domestic and traditional architecture, this chapter focuses on the bigger picture of how large, densely populated cities are able to transform and mitigate the adverse effects of a viral pandemic. Taking a look in the health of a city’s population, through such initiatives as active travel, reduced congestion, health incentives, etc., as well as the issues surrounding food systems when supply chains are broken, which often lead to community awareness and cooperatives, the aim here is to investigate and to attempt to understand the social and structural challenges urban planners and strategists will have to face due to the pandemic.

Chapter 3 – Breathing cities

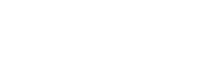

The transfiguration of our cities and urban infrastructures into sustainable and healthy communities is one of the key determinants of health as outlined by The Settlement Health Map, a system used to integrate human health and sustainability into urban planning, and in part developed during Phase IV of the World Health Organization’s Healthy Cities programme. Such proposals include the propagation of green spaces and urban parks, where people can participate in active travel, socialise with friends, and exercise freely. However, this is not so much a new idea and is inherent in the history of public spaces, with the integration of green spaces in town planning proliferating in the Victorian period in England where large swaths of the population’s health had been damaged by pollution, poor hygiene. poverty, and disease. These green spaces offered a respite to the local population and were said to have health-giving benefits. Whilst a minority were able to retreat to the countryside (much like they have done today) those confined to the city only had access to its parks and green spaces to counter the damaging health effects of industrialisation and to escape the higher probability of disease and infection through densely populated neighbourhoods. This is important to mention since throughout the pandemic those living in poorer neighbourhoods suffered higher transmission and subsequent mortality rates of Covid 19 than the overall population.

The Settlement Health Map. Reproduced with permission from Barton H and Grant M 2006

And thus it is clear that the integration of health into urban development and planning is an effective way to successfully plan for a pandemic. Such initiatives of course can already be seen and have been in existence for far longer than this previous year. And yet it is true for some that the effects of Covid 19 have been a determining factor in these initiatives taking on an increased intensity and momentum. In Pontevedra, in Spain there has been an increase in pedestrian areas, whilst the speed limits have been set for cars in order to encourage active travel and mobility. This encourages social movement and reduces air pollution, which of course is fundamental to respiratory function. Meanwhile, in Loule in Portugal, sporting events have flourished, students have been provided with free bicycles to commute to and from school, and online walking and cycling routes have been distributed freely. And in a new sustainable and nature-based approach in Bradford in the U.K., where one quarter of its population are under the age of 16, the streets surrounding local schools have limited traffic in order to make the neighbourhood friendlier to children and young people. ¹

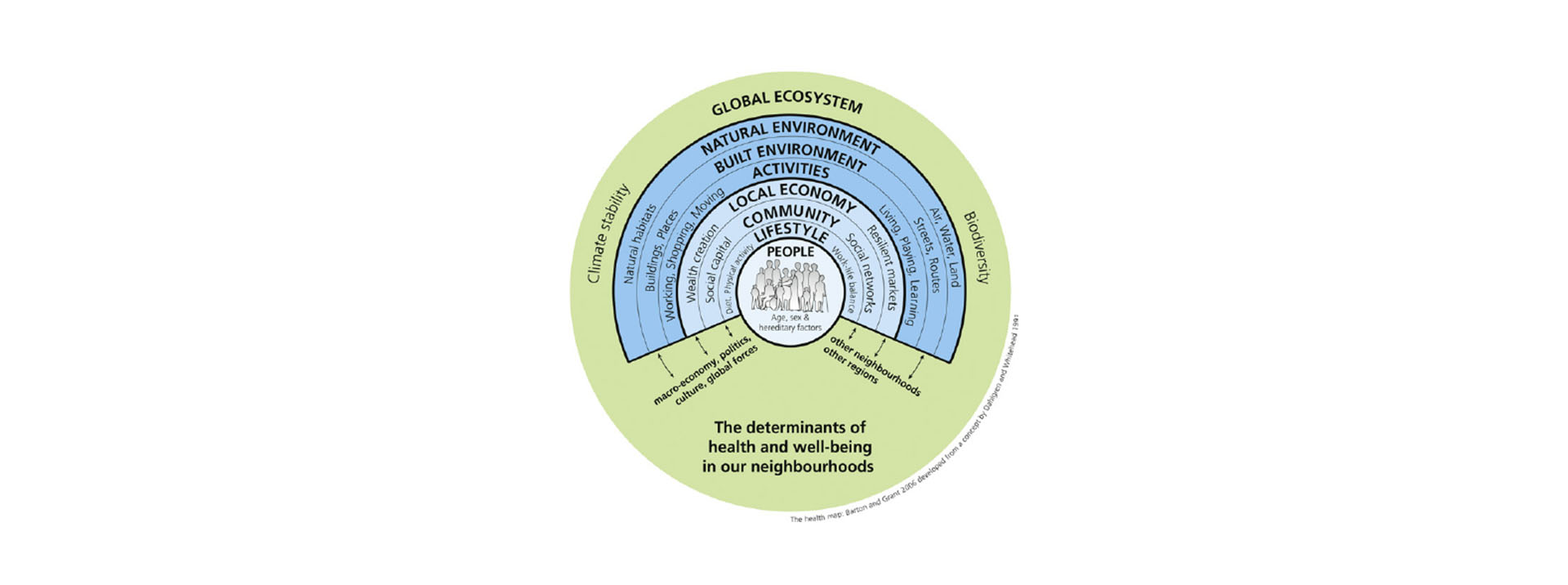

Such initiatives as these are key in promoting the collective health of a community and reducing airborne particulate matter. In 2012, the Canadian Public Health Association reported that it costs 27 times more to achieve a reduction in cardiovascular mortality through clinical interventions than it does through public spending on incentivising active travel ². Meanwhile, Copenhagen estimates that the city saves 12m dollars in healthcare from just a 10 percent increase in cyclists ³ . Cycling is a particularly effective way of improving public health, unburdening pressure on health services, diverting traffic from the street, and for allowing socially distanced commuter travel. In Bogotá the city is opening up its 22-mile Ciclovía network, a system of streets normally closed to cars on Sundays, during other days of the week, whilst Mexico City proposed plans for 80 miles of temporary bike infrastructure to alleviate the risks of public transportation use and facilitate mobility in the megalopolis of more than 21 million people. 4

The contribution of smart cities has also come into play due to the pandemic, with several technological innovations being used to slow the spread of the virus. In Newcastle in the U.K. an Urban Observatory monitors pedestrian movement and air quality. Meanwhile, the Track and Trace app can even be said to be as much an urban development strategy as it is a health and public service one.

If we are to take the estimate that by 2050, 68 percent of the world’s population will be living in cities 5, then that has to be a systematic approach which will allow for people to interact with the outside world and their neighbours, friends, families, safely, should another crisis arise again, or if this current one should continue. Recently, Italian studio Stefano Boeri Architetti (who for many years have been working towards urban and vertical reforestry to combat the environmental crisis) and Albanian architecture studio SON-group have unveiled a masterplan for 12,000 residents in the district capital of Albania close to the Tirana riverside. By making extensive use of rooftop gardens as gardens that can be used by all residents as green spaces for domestic agriculture and/or leisure, as well as of plantlife which will be incorporated into the communal areas, building facades, and pedestrian bridges, their plan emphasises the importance of outdoor spaces, in both public and private spheres. By implementing this, the common areas will expand, bringing the outside in. Never has a sentiment seemed so needed. Other notable examples which follow the same line of thinking as Stefano Boeri Architetti include the Madrid Rio Project and the High Line in New York, where communities can come together in a green urban setting.6

Tirana Riverside, project designed by Italian architect Stefano Boeri together with SON Group © Stefano Boeri Architetti

Expanding on the idea of rooftop gardens and communal gardens, the development of urban food supplies and systems is instrumental in the future of urban spaces. The pandemic disrupted many global food systems and brought to light how reliant urban networks were in importing food from distant sources. As 70 percent of all food grown is now destined for urban consumption, urban planners and food strategists are now at odds to ensure the food security of a population when supply chains are broken. The solution can be to have pockets of communities coordinating and working together to distribute food to their neighbours. And in particular, fruit and vegetable box schemes and home growing have increased due to newfound awareness of food shortages (one notable example being with community responses to the failure of the government in providing free school dinners in England). In Quito in Ecuador, there has been a rise in family-scale forms of food distribution. And in Kitwe in Zambia, the government has actively encouraged small scale producers to serve the local community and to negate the reliance of imports. And in Canada, community gardens in Toronto were deemed an essential service to the city, whilst the Ontario Food Terminal provided free access to small-scale food producers 7. Such initiatives bring forth the argument of a more sustainable and manageable food system. In terms of architecture and urban planning, it is important to register such necessities and make use of available space for food production.

Workshop A Green House at Boisbuchet led by French-French-Lebanese architect Lina Ghotmeh, 2017, © Mariana Lopes

In 2017, French Lebanese architect, Lina Ghotmeh, and her students, designed and constructed a greenhouse which sits on the central axis of the kitchen garden of Domaine de Boisbuchet. It is a roof with one side smaller and lower that ducks out of the Atlantic winds from the west while collecting rainwater in the close-by reservoir. The stabilizing truss inside accommodates shelves for pots and provides opportunities to suspend crops for drying. All the produce from the greenhouse and the kitchen garden is then used in the central kitchen to cook for residents and guests on the Domaine. Each season, Boisbuchet then welcomes a garden trainee or intern to run the garden in association with the chef, head gardener, and kitchen team. The trainee often is able to experiment on alternative methods of growing, such as permacultural methods wherein the produce is able to grow alongside wild plants. The food produced varies from year to year, but often consists of lettuce, tomatoes, courgettes, strawberries, as well as edible flowers and a wide variety of herbs. Additional ingredients such as bread and meat are then sourced from the local community. In September apples are then harvested from the orchard and are used to make over 3,000 bottles of apple juice, which are then sold back into the local community.

The history of Boisbuchet is also deeply tied to traditional and sustainable agricultural farming techniques and methods of self-sufficiency, whilst a sizable portion of the design and object collection is dedicated to the Amish community, such as three large carts from Pennsylvania in America. There is also a family of horses born on site once able to help plough the fields when the Domaine was first purchased over 30 years ago. Of course, such examples are not possible to emulate with a lack of resources, but the efforts demonstrated can inspire those who have the time and land to make such a commitment to their communities. And whilst it is difficult for people to find the time and space to grow their own food, there are also possibilities of cultivating indoor gardens. Not only can you then produce your own food, but indoor plants act as filters, which take in carbon dioxide and release oxygen.

Lina Ghotmeh’s Stone Garden apartment building in Beirut has balconies which invite nature to climb up to the skies of individualizing each housing floor, whilst these openings are drawn as mass-subtractions to become enjoyable planted `balconies’. In addition, Lina’s latest proposal for an office building “ECOmachine” generates 20% more workable space through its use of terraces, gardens and loggias on each floor. These new spaces serve as meeting points for collaboration and interaction, as well as hybridising different functions and needs in architecture. 8 Such considerations are only continuing.

Ultimately, reactions to the pandemic in the urban setting will be interdisciplinary in nature, with many disciplines needed to combat the prevailing problems cities have today in available space and infrastructure. Architects, urban and town planners, governmental bodies, scientists, sociologists, and the local community, will have to work together in order to create a healthier urban habitat. This habitat should encourage social movement and prioritize active travel over increasing traffic and automobility, which harm the air quality and lead to a sedentary immbobile population more vulnerable to complications as a result of infection. Generating a robust supplementary food system is also paramount to avoid shortages and malnutrition.

Stone Garden Housing in Beirut designed by Lina Ghotmeh Architects © Iwan Baan

For the final chapter, we will be looking more in detail to space, and more accurately the circumstances surrounding the confinement. How best prepared are people following government orders to stay inside? Surely, the standards of living and the architectural motivations are fundamental to societal and individual wellbeing in domestic isolation.

Stay tuned!

Kester Farrell is a British architecture and design research assistant, currently undertaking a six month research project at Domaine de Boisbuchet.

- https://urbact.eu/

- https://www.cpha.ca/making-economic-case-investing-public-health-and-sdh

- https://ec.europa.eu/transport/sites/transport/files/cycling-guidance/smart_choices_for_the_city_cycling_in_the_city_0.pdf

- https://www.wri.org/insights/biking-provides-critical-lifeline-during-coronavirus-crisis

- https://ourworldindata.org/urbanization#:~:text=By%202050%2C%20it’s%20projected%20that,to%20be%20higher%20than%20urban.

- https://www.stefanoboeriarchitetti.net/en/project/tirana-riverside/

- http://www.fao.org/uploads/pics/City_Region_Food_Systems_to_cope_with_COVID19_and_other_pandemic_emergencies___12.05.2020.pdf

- https://www.linaghotmeh.com/en/stone-garden-el-khoury-foundation.html