Future forward: Design with/for/by animals

Workshop Slow Down Please at Boisbuchet led by French designer Marlène Huissoud, 2019 © Martina Orska

There are 8.7 million species on the planet, and we are but one. So, what do we do when a client has several legs and eyes, feathers and beaks, or clawed feet? The questions we must ask ourselves: What role do animals have in the design of their spaces? And is it even possible that we can design with them, rather than simply for them?

For if animal architecture can be defined as simply architecture made for animals, such as pens, cages, enclosures, stables, factories, then why do we still feel the need to redress our relationship to our fellow species? In truly designing for animals, should the function be for ourselves or for the animal? Or perhaps both.

Here are some examples of architecture – ancient and contemporary – that examines these questions and poses possible answers.

It’s a Dog-Eat-Dog World

Organised by Kenya Hara, the Creative Director of MUJI, ‘Architecture for Dogs’ presents several works by architects and designs for dogs. As our closest companions, they live in our own world, our own architecture. This exhibition, held at the Japanese House in London, presents a new perspective, reversing the human-dog balance, and re-examining how our architecture is traditionally made for non-dog use.

Here, Konstanti Grcic’s mirror for poodles (since they are the only dog species that recognise their reflection) meets Shigeru Ban’s cardboard tube maze for papillons, and Sou Fojimoto’s interior dog house that doubles as a furniture shelf.

Papier Papillon by Shigeru Ban © Architecture for Dogs

So what do we do when designing for creatures that go unseen, that we cannot pet or play with? Ones that seem so innately different and distinct that we cannot gather the emotional resources to think for and with them? One-third of the world’s insect species are endangered and the total mass of all insects is declining by 2.5% a year. Yet we continue to intensify our agriculture and develop our urban settlements.

This was a problem addressed by French designer Marléne Huissoud. Made for the wildlife of London, helping insects to find a suitable refuge within the city, Marlène developed together with scientists Robert Francis and Mak Brandon from King’s College London a series of furniture for bees, butterflies, and other pollinating insects.

Meanwhile, humans were asked to ‘Please Stand By’

On the right, The Chair from the collection ‘Please stand by’ by Marlène Huissoud

currently presented in the exhibition ” Landscapes of design, Women at the heart of the Domaine de Boisbuchet “, 2022. Frac Centre-Val de Loire. Photo: Pablo Sevilla

The pieces are made of unbaked clay with a natural binder for weather protection. Huissoud and the scientists opted for colours that insects are naturally attracted to such as whites and greys, whilst the surfaces are perforated with 5–10-centimeter holes for the insects to check-in.

Currently, Marlène’s Insect Hotel is on view at the exhibition ‘Landscapes of Design, Women at the Heart of Boisbuchet’ at the Frac Centre-Val de Loire in Orléans. Here it fits alongside Farm 432 BETA, Katharina Unger’s insect breeding farm used to grow mealworms as an alternative to industrial meat production.

Meanwhile, in order to face the problem of the disappearance of bees, French designer Juliette Dorizon proposes a new typology of bee hives, one that allows an approach of apiculture that is more respectful of the bees. Such a typology was installed along the grounds of Domaine de Boisbuchet. Its octagonal shape is reminiscent of the hollow tree trunk where swarms of bees live in the wild.

La Ruche, is a new typology beehive conceived by Juliette Dorizon, in reference to the Eustachian tube, a small cone located between

the nose and the ear that allows us to hear and smell the bees © Sandra Plessing, Pablo Sevilla

But animal architecture is nothing new!

Dating back 800-years and reaching up to 18 metres, mud-brick towers have been built across the Middle East, most notably in Iran and Egypt. As a practice that has gone so far back as 8,500 years ago when early man first domesticated the rock dove, and with hieroglyphs depicting the raising of pigeons on the walls of the tombs of Egyptian pharaohs, these dome-shaped structures were built to farm up to 14,00 pigeons.

As a variation of the dovecote or the French colombier (that had been made with wood or stone), no two Middle Eastern pigeon towers are built in the same way. They are an example of an isomorphic vernacular technique, with the know-how passed from generation to generation. The tower walls are often slanted to allow the guano (or pigeon droppings) to amass. High in phosphorus and nitrogen, it is then collected and used as a low-tech fertiliser on melon and cucumber fields. With the outer drum buttressed internally to prevent collapse, the tower consists of a honeycomb of nesting perches for the pigeon, whilst the size of the hole for the pigeons to enter is too small for predators….

That is until they are stuffed with cracked wheat and roasted in an Egyptian delicacy called hammam mashi.

View of three Middle Eastern pigeon towers. This summer, emirati architects Rashid and Ahmed bin Shabib

will build a traditional pigeon tower as part of a workshop at Domaine de Boisbuchet

Designing with Animals

Rethinking how we design and for whom is always a fruitful exercise. But a collaboration with a client is always necessary to achieve optimal results. The same can be said in our relationship to the animal kingdom. Should we insist on designing for them rather than working with them? And what right do we have when several species are already competent architects and builders in their own right?

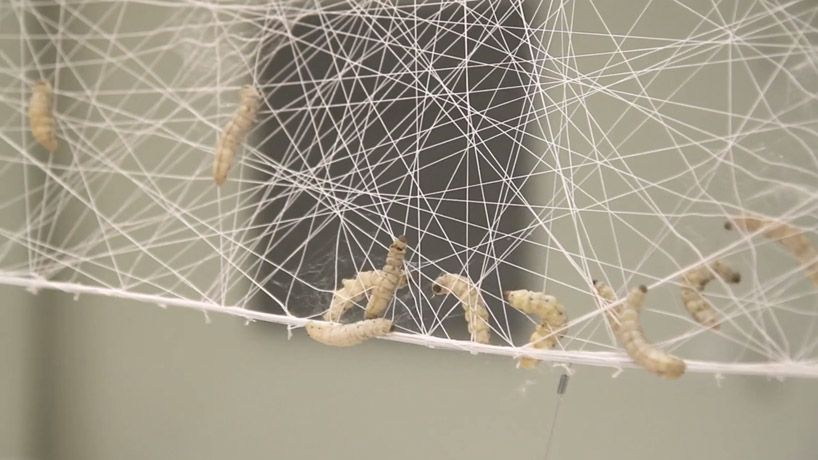

Such a collaboration was shown in Neri Oxman’s Silk Pavilion, first developed in 2013. Traditionally, silk is harvested by boiling the larvae of silk worms alive in their cocoons to extract silk thread. This pavilion instead allowed the silkworms to live and metamorphosize in relative peace. Taking the form of a three-metre wide dome, constructed over three weeks with a flock of 6,500 live silkworms assisted by a robotic arm. Each silkworm spun a single silk thread filament that is about 1km long. Combined, the silkworms produced a dome-shaped thread as long as the Silk Road. Video

Neri Oxman’s Silk Pavilion at MIT Media Lab in 2013. All images and videos courtesy of Neri Oxman and The Mediated Matter Group

This summer, the workshop ‘Building an Arab Pigeon Tower’ will run at Domaine de Boisbuchet from June 26 to July 2, led by Dubai-based urbanists Ahmed and Rashid bin Shabib. Whilst Marlène Huissoud’s explorations into creating habitats for wildlife in her workshop ‘What Do We Do Now’ will run from August 14 – 20.

For more information on this year’s workshop season, visit our website

https://www.boisbuchet.org/workshops/2022-season-repair-recharge-reset/

Kester Farrell is a British architecture and design research assistant at Domaine de Boisbuchet.